Even in these times of lockdown we are permitted to take outdoor exercise once a day. I take mine in the form of a walk – a constitutional as an earlier generation would have called it. I’m lucky in that I live beside the Thames in South-west London and there are many pleasant routes I can take starting straight from my door. One of my favourites is to start off following the Thames Path and then go along Queen Elizabeth’s Walk, passing the London Wetland Centre (now closed like everything else), to reach leafy suburban Barnes with its village green and pond. The buildings on my right as I go along the section of Church Road once called Lowther Parade are impressive. First up is the Olympic Cinema, Café and Dining Room built as an entertainment centre in 1906 and from 1966 until 2009 famously used as a recording studio by bands such as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin. Next to the cinema is the 18th century building, Homestead House and beside that the moderner Homestead Cottage with the parish church, St Mary’s, a little further along. The distraction of these buildings to my right had always, up until the most recent occasion I did this walk, caused me to miss a memorial stone to the left of the pavement outside Homestead Cottage. The stone has a Victoria Cross at its top and is inscribed ‘Captain Alfred Carpenter, Royal Navy, 22nd – 23rd April 1918’. No additional information is provided so I decided to try to find out who Alfred Carpenter was and what happened on those days and why the memorial is placed on Church Road, Barnes.

A quick Google search provides a simple answer to the third question. Barnes was his place of birth in 1881. Some sources say he was born in Byfield Cottage. As the information board outside the building which is now the Olympic Cinema, Café and Dining Room tells us that it was built on the site of Byfield House, then it is perfectly reasonable to assume that Byfield Cottage was nearby and that the memorial stone is very appropriately sited. Some brief biographical details are that he was born into a family that had associations with the Royal Navy dating back to the Napoleonic era and that he joined up as a midshipman in 1898 and rose through the ranks to become a vice-admiral (retired) in 1934. In World War 2 he commanded the Wye Valley section of the Gloucestershire Home Guard. He died in St Briavels, Gloucestershire in 1955.

The Royal Navy website turned out to be the best source of information on the memorial stone and the events of 22nd – 23rd April 1918. Carpenter, then ranked Commander, captained HMS Vindictive, a cruiser which led a raiding party on the port of Zeebrugge. The object of the raid was to block the harbour to prevent German submarines from leaving the port. The action was ultimately unsuccessful in that the waterway remained blocked for only a few days, but it was initially hailed as a triumphant incursion into German-held territory and eight VCs were awarded, including the one for Alfred Carpenter who was selected to receive the honour by a ballot of his fellow officers. Paving slabs to commemorate all eight who were awarded the Victoria Cross for their part in the Zeebrugge raid were installed near to their homes on the centenary of the action.

Carpenter wrote a book about the raid called The blocking of Zeebrugge, which was published in 1922.

Further information –

The Barnes Trail – http://www.barnesvillage.com/barnes-village-trail.html

The London Wetland Centre – https://www.wwt.org.uk/wetland-centres/london/

Olympic Cinema, Café and Dining Room – https://www.olympiccinema.co.uk/history

St Mary’s Barnes – https://www.stmarybarnes.org/history-architecture/

Alfred Carpenter’s memorial stone – https://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/news-and-latest-activity/news/2018/april/17/180417-zeebrugge-heroes-honoured-with-ceremonial-paving-stones-in-the-capital

Timeline of Alfred Carpenter’s life – https://livesofthefirstworldwar.iwm.org.uk/lifestory/6889414

Alfred Carpenter’s VC citation – https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30807/supplement/8585

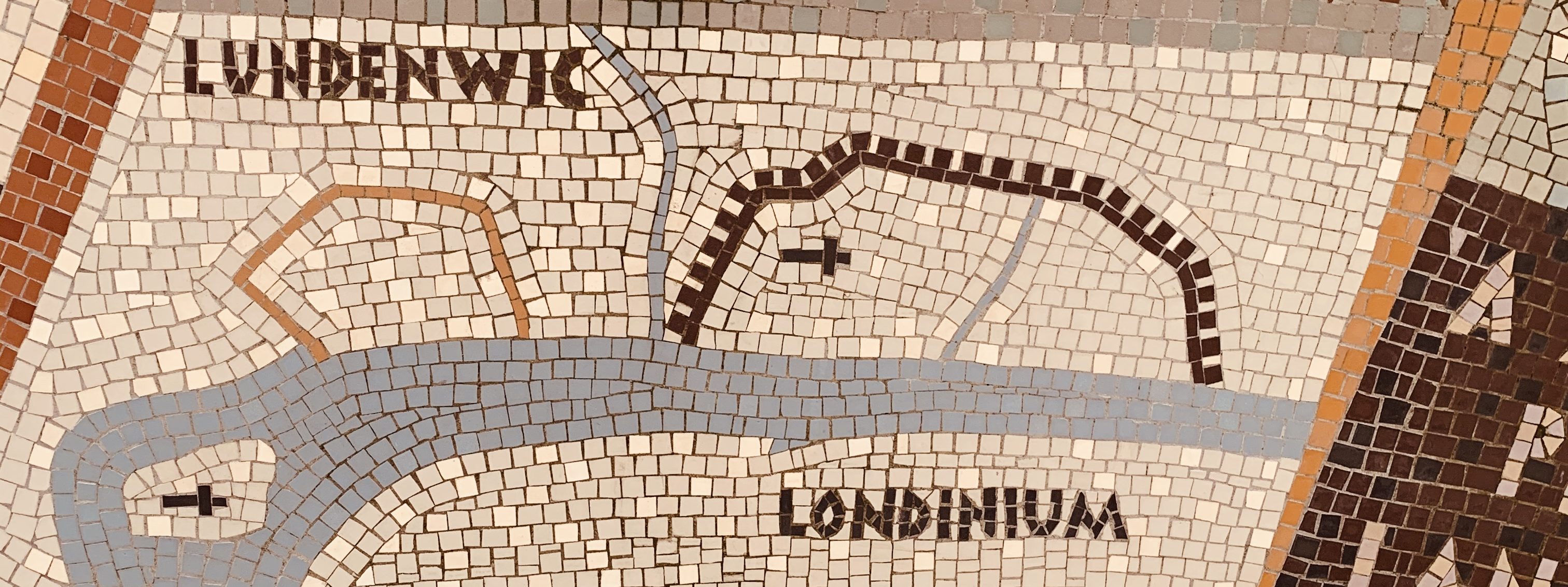

image [Image taken from the Royal Navy website]

Paul Stokes

Simon Stewart

Simon Stewart